Keith Hennessy, MFA, PhD, is a frolicker, imperfectionist, and witch working in the fields of dance, performance, activism, affordable housing, and sexual healing. Raised in Canada, he has lived in Yelamu/San Francisco since 1982, and tours internationally.

Hennessy’s work is interdisciplinary and experimental, motivated by anti-racist, queer-feminist, and anarchist movements. He engages practices of improvisation, ritual, play, and protest to respond to political crises and personal unrest. With a focus on the poetics and politics of collaboration, Keith has shared power and creativity with Ishmael Houston-Jones, Annie Danger, Sarah Crowell, Snowflake Calvert, Marc Kate, Meg Stuart, Peaches, Guillermo Gomez Peña, Jassem Hindi, jose abad, Alley Wilde, Gerald Casel and more. Hennessy directs Circo Zero and was a member of Contraband with Sara Shelton Mann. Hennessy is a co-founder of CounterPULSE and 848 Community Space. Awards include Guggenheim, USArtist, NY Bessie, and SF Izzies. Venues include Impulstanz/Vienna, Kampnagel/Hamburg, SF MOMA, The New Museum/NY, TBA Festival/Portland, Velocity/Seattle, Ponderosa/Germany, YBCA, CounterPulse, CORE/Atlanta. Keith teaches widely at universities, festivals, and independent studios. www.circozero.org

Keith Hennessy: Hi everyone. Before we start, can you give me some context? What’s guiding the conversation today?

Jeff Jones: We’re interviewing people about the transformation of San Francisco’s arts community after the early 1990s controversies about the City’s arts funding policies. Events from the late 1980s and early 1990s radically altered the City’s approach from supporting big-budget organizations such as the Symphony, Opera, Ballet and Big museums that served primarily affluent white audiences to funding arts organizations rooted in all communities that comprise San Francisco’s population.

This project is informed by the queer community’s feminism and militancy. Keith, you’ve always demonstrated a strong connection to both of these values, and that’s the specific reason we wanted to interview you. For many years, you have been involved in activities where politics and the arts intersect. If you have any insights on how and why this process has evolved since the 1990s, that’s really what we’re looking for here.

B&A: We are also concerned that the people who made this arts funding history started dying before this history has been documented or preserved. So we are creating this archive as a historical record. With all the push-back against diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI), we think it’s important for artists, elected officials, educators and community leaders to be able to say, “Hey, they did this in San Francisco. Maybe we can do it here too.”

B&A: We are also concerned that the people who made this arts funding history started dying before this history has been documented or preserved. So we are creating this archive as a historical record. With all the push-back against diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI), we think it’s important for artists, elected officials, educators and community leaders to be able to say, “Hey, they did this in San Francisco. Maybe we can do it here too.”

And we have also witnessed and experienced your incredible contributions to sexual politics, sex education, sex worker rights and sex positive culture. Keith, you came from a small coal mining region in Canada, correct?

KH: Not coal– nickel. I grew up in Sudbury, Ontario. My hometown had the biggest nickel mine in the world from the 1930s to the 1970s. The entire post-WWII boom in the US was built from steel that is alloyed from the nickel from my hometown.

B&A: How did you go from that mining region to where you are right now?

KH: Who knows why some of us escape our hometowns and some of us don’t. I left Sudbury because I had to. Before I had any language to understand the kind of artist that I was to become, I knew that whatever I was, I didn’t belong in Sudbury. I dreamed of moving to a big city from the age of 11 or 12 years old. The furthest my mind could imagine was Toronto, 5 hours away.

I started dancing in high school. I was being called a faggot every week and it got worse and worse. No classes or lessons, but I was a competitive social dancer. I worked with one partner and we would rehearse in the hallways and after school. In late high school, we started escaping to Toronto and going to clubs, including gay clubs, because that’s where the best dancing was. We were underage.

The year after high school, I was so fed up with being told what to do that I worked 3 jobs, saved up all my money and moved to Europe for a year. I quickly realized I was a small-town kid with no idea of how the world functioned. I didn’t know how to be there. Then I saw modern dance. I saw Nureyev and friends (that was the name of the concert) in Paris. My path got clearer and clearer. Mostly I spent time in France, because I spoke French. I grew up in a bilingual-ish town and had taken French classes in high school. I wasn’t amazing at it, but I was functional. I also went to Germany and other places, but that was harder.

When I was in France, I learned that the cool city in Canada was not Toronto, but Montreal. By then I understood class warfare and I knew I needed a college degree. So I went to university in Montreal, which is where I really started dancing. There’s a very vibrant dance community there.

I also became an anarchist in Montreal, but I didn’t want to be an anarchist with a college degree so I quit in my last semester of school, just so I wouldn’t have the degree or any other validation from the state. When I left university the first time, I thought to myself, ‘I will never come back except as a teacher, to change the system from within, and to work with students.’ I kept to that.

B&A: But didn’t you get a Ph.D. at UC Davis.?

KH: Not until I was in my forties and fifties.

B&A: Was that experience useful for you?

KH: Totally. I was raised in a family where we were supported to think big. I had older brothers and sisters who charted the path. Some of them went towards politics, or psychedelics, or travel… and by the time it was my turn, as the fifth kid, I was out of there. None of them traveled as far away as I did. I realized I could live anywhere in the world.

After Montreal, I hitchhiked with a buddy to a juggling convention in California. I decided I was going to stay in San Francisco and be a dancer, and that’s what I did. If you’re an anarchist, you disrespect nation-state boundaries. So when I moved to the USA, I stayed here illegally for the first 10 years.

B&A: What was your UC-Davis dissertation about?

KH: I called it Ambivalent Potential. I focused on the 1970s and ended up whittling it all the way down to a queer and critical race analysis of contact improvisation. I looked at the internal tension within post-sixties politics: they could be liberatory or they could reproduce hegemonic or normative structures. Contact improv had all the ingredients to be one of the most radical dance technologies, but at the same time it was predominantly practiced by white people.

How did it happen that a group of mostly straight white people could go into this space where everyone’s included, whether it’s the rave community or the Burning Man encampment, where alternative technologies look like they have liberatory potential but ultimately continue to reproduce heterosexual white norms? I’ve always been wrestling with that question about supposedly alternative cultures so that’s what I did my dissertation on.

B&A: Have you published it?

KH: Only as a ‘zine, but with over 1000 copies sold and probably 2000 copies in circulation.

B&A: Which artists or people inspired you the most in your teens and twenties?

KH: I didn’t know many artists in my teens and twenties but I had an uncle who was a figurative sculptor, aka naked bodies. He was the first professional artist I ever knew. He was the freak of the family and lived further from middle class norms. When I moved to Montreal I was very inspired by Margie Gillis, a super emotional solo dancer and by a group called Mime Omnibus, who worked at the experimental edge of physical theater through mime with rich visual images and non-narrative dream structures. I didn’t have a mentor until I moved to the Bay Area and worked with Lucas Hoving when I was 22. Lucas, a former dancer with the Jose Limon Company, moved to the Bay Area from New York when he was an older man. His rigorous improvisation and composition classes left a deep impression on me.

JJ: What year did you arrive here?

KH: 1982.

JJ: The first time I saw you perform, Keith, was in 1989. You were with Contraband, right? I think I saw you dance at the Isadora Duncan Awards.

KH: The Izzies, yeah.

JJ: When I first saw you, you were dancing with Sara Shelton Mann’s Contraband. Could you tell us what Contraband pioneered as a dance company that nobody else did?

KH: I think Sara Shelton Mann has had a profound effect, not just on San Francisco’s dance community, but also on dance as both a political act and as a healing art. Through a feminist lens you can track her career’s trajectory and her significance as a world-changing artist. She’s one of these classic, complex artists who has always been afraid of political identities and would probably never refer to herself as a feminist, even though last year she made an extraordinary work about reproductive justice that referenced the illegal abortion she had 60 years ago in the American South.

Sara’s body and mind know these stories very deeply and she has traveled a very feminist route. She has worked in male-dominated scenes and yet still found ways to assert herself and create her own path. She’s worked with extraordinary feminists such as the internationally recognized, pioneering lesbian feminist dance company, The Wallflower Order.

When Wallflower broke up and evolved into the Dance Brigade, Krissy Keefer and Nina Fichter hired Sara to make new work with them, and I got to be Sara’s assistant. They were the very first people in the local dance community to embrace Contraband. They brought us into Furious Feet: The Dance Festival for Social Change that they organized in the 80s and 90s.

When Wallflower broke up and evolved into the Dance Brigade, Krissy Keefer and Nina Fichter hired Sara to make new work with them, and I got to be Sara’s assistant. They were the very first people in the local dance community to embrace Contraband. They brought us into Furious Feet: The Dance Festival for Social Change that they organized in the 80s and 90s.

Krissy and Anne Bluethenthal, two feminist queer women choreographers who lead with politics, created the first Lesbian and Gay Dance Festival. When they invited me to participate, I invited my two straight collaborators from the Contraband era — Jess Curtis and Jules Beckman, and we made this legendary dance piece Ice Car Cage with a driverless moving car that continues to be celebrated by people all over the world.

The work of many artists is deeply informed by feminism, but at the same time, there’s endless push-back. Not many young artists respond favorably to the word feminism because it conjures up the white feminists who resisted the brilliance and leadership of women of color, specifically Black women, among other conflicts about sex, sex work, porn, penetration, art…

As a teacher, I constantly have to walk students through white feminists who were intersectional before the word even existed. Socialist feminists like Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English were always lifting up intersectional politics because they were deeply involved with socialism and hard-left 1960s politics. They were always thinking about class and race. Now a weird trip is going on with dissing terms such as “feminism” and even with “dyke” or “lesbian.” Simultaneously, I’m working with some younger queer and femme artists who really want to know, “Who were the queer women in Bay Area dance before us?”

With Clarissa Dyas, Alley Wilde, and Queering Dance Festival we are producing a public talk called Dykes in Dance, which is going to happen June 18 in Berkeley. There was definitely push-back from some of our younger colleagues who are very hesitant to embrace or see themselves in community with lesbians or dykes, as if these historical terms meant exclusion to them. When they hear “lesbian,” they assume those are the people who excluded trans women, or bisexuals, or sex workers, and the people who didn’t embrace Audre Lorde.

Anyways, many of the artists who were attracted to Sara were very politically engaged. Kim Epifano came out of the Dance Brigade. I came out of different anarchist scenes. Nina Hart was also very involved in anarchist and feminist politics. I was obviously queer from the late 80s onwards, and was extremely involved in ACT UP and Queer Nation; both crucial to the queeruption aka cultural and political uprisings in response to AIDS.

Anyways, many of the artists who were attracted to Sara were very politically engaged. Kim Epifano came out of the Dance Brigade. I came out of different anarchist scenes. Nina Hart was also very involved in anarchist and feminist politics. I was obviously queer from the late 80s onwards, and was extremely involved in ACT UP and Queer Nation; both crucial to the queeruption aka cultural and political uprisings in response to AIDS.

Those perspectives were always embraced in Contraband, but if you tried to pin down the group’s actual politics, you couldn’t do it. It was a liberatory kind of dancing. When you saw it, you felt like these people were making a new world: they were bringing more freedom to the body, and to each other, and to their communities. Contraband’s dancing, which normalized contact improvisation’s genderless roles and women-lifting-men worked through and against the structures of misogyny.

Sara is of legendary significance because she impacts all the political artists, from the people at NAKA Dance Theater doing really important work with immigrants and refugees to the Black queer collective “rupture.” Sara has worked with and mentored 4 or maybe all 5 of them, including collaborations with them in her own work. But Sara herself does not fit into any of the dance categories or identity categories or arts for social justice / artist as social work categories that today’s grants demand.

JJ: Sara and I moved here in the same year—1978– and we’re the same age. Every time I saw her work, I could never figure out how to categorize it. It felt like there was some Buddhist overlay that I couldn’t put my finger on. She’s always had a really bad approach to fundraising: she writes descriptions of her work that only she can understand.

KH: I think she just doesn’t have the capacity to be a successful fundraiser because she grew up with extreme trauma and didn’t graduate from college. She doesn’t feel like she’s one of those classy people who can get through the gate.

In terms of the funding world’s changes, Sara couldn’t get much funding in the 80s or 90s because she was too experimental, not strictly dance, and that kind of work was rarely valued by grant panels, especially in SF compared to NY. Now that kind of work can be valued, but she can’t get funding because she’s white, old, cis and doesn’t use the required politically correct language to describe herself or her working process.

The fact that you can’t categorize her should be lifted up as what’s so exemplary and radical about her. The fact that you can’t figure out her exact relationships to people is the queerest thing about her. The fact that some of the more politically engaged artists to ever come out of dance in San Francisco, Berlin, Stockholm, Paris and Mexico City are deeply impacted by Sara Shelton Mann is significant. And yet she can’t get funding because she can’t connect her work to any particular political stance, social service, or any fundable dance style. In California and across the US the arts funding agencies have weaponized shallow versions of racial diversity and woke language and used it against actual political artists.

I’m fairly successful at writing grants because I lie through my teeth and use bullshit language about race that embarasses me and my collaborators. I have to apologize to my collaborators of color and ask, “Do I have your permission to prioritize your role in the piece over mine, to overly emphasize your skin color and your historical background so that we can get money?”

These experimental queer Black, Filipino, Asian, Latino, and Indigenous artists go, “Yes, you get the coin, and you can say (almost) whatever you want about me. We know that arts bureaucracy is bullshit.” But the problem is that those of us who are actually political radicals and anti-racists helped create that language. You, Jeff, helped create that language. Because of you and me, especially you, so many new artists of color, queer artists of color, have been brought into the funding scene.

But at the same time, the language we created is now being used against us. It’s paying lip service to anti-racism and decolonization, saying that they’re going to lift up artists of color when they’re never actually going to give them enough money to live off, to support a child, to retire. In fact, they’re reproducing segregationist language, encouraging the most inflexible, separatist, and essentialist ideas about racial identity, and that language is then reproduced in the artworks all around us.

JJ: Yes, it feels to me like we are back to where the arts world was in the mid-1980s, when we had words like “multiculturalism” and nobody knew what it meant. The California Arts Council is a really great example. They have a so-called “peer review” process, but it’s not the peer review system of 40 years ago that was facilitated by specialists in the arts discipline, who knew the significant artists and organizations and who was empowered to interrupt and correct any mis-statements of facts made by the panelists.

JJ: Yes, it feels to me like we are back to where the arts world was in the mid-1980s, when we had words like “multiculturalism” and nobody knew what it meant. The California Arts Council is a really great example. They have a so-called “peer review” process, but it’s not the peer review system of 40 years ago that was facilitated by specialists in the arts discipline, who knew the significant artists and organizations and who was empowered to interrupt and correct any mis-statements of facts made by the panelists.

Today, to determine who the agency should fund, CAC and the Arts Commission rely on inexperienced panelists who often don’t know what they’re talking about, and the facilitators are supposed to remain silent. As a result, funding decisions only minimally take into account the quality or the originality of the art being created or the history of the organization. Unless you can employ the jargon of cultural equity and inclusiveness, what you’re doing as an artist becomes irrelevant. Moreover, last year CAC awarded a $60,000 grant to a non-profit with an operating budget of less than $10,000 because the process no longer takes into account the applicant’s capacity to manage the funds.

KH: I’m totally fine with giving artists and small non-profits huge grants. $60,000 is not very much money. If a tech worker of the same age with less experience in their field than any dance maker had a good idea they’d be given millions in venture capital. But CAC’s decision-making process is almost completely irrelevant. To get a better understanding of what was happening, I volunteered to be on one of the California Arts Council’s review panels. The pay was incredibly low and I confronted them about the absence of a decent wage. CA’s staff wrote back and said, “Well, we just do what we can with state funding, blah, blah, blah.” And that’s bullshit. If they wanted to fund excellent art with high community impact, they could pay more. Instead, they operate a totally bankrupt decision-making process and label it cultural equity.

Being on a review panel showed me how it works: CAC recruits low level arts administrators who have full-time jobs. When these folks serve on the panel, CAC’s meager stipends supplement their existing salaries. As a result CAC can continue to easily recruit review panelists with limited knowledge and experience instead of attracting working artists or seasoned and knowledgeable reviewers.

The process takes place entirely on Zoom and there’s no personal contact allowed between the panelists. You can’t even message each other. I was on one panel where you couldn’t see who else was there and I had to ask, ‘Could you please reveal the other people who are on the panel?’ They don’t want you to talk to each other. Some bureaucratic CAC staff member has conned the field into believing that this system produces equity and otherwise there will be bias. In “the old days,” being on a grant panel meant debating the proposals, learning from folks with different perspectives, even arguing. Now it’s all scoring. Data wins. As if increasing bureaucratization and dehumanization doesn’t create its own bias. We’re not that far away from AI grant reviewing.

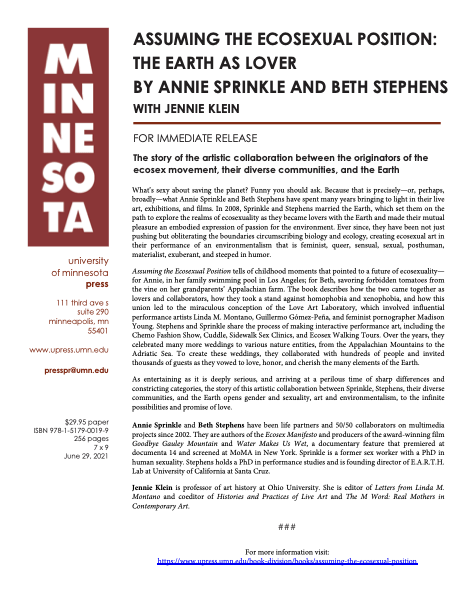

JJ: Beth and Annie recently applied to the SF Arts Commission for a Cultural Equity Grant and the panelists tore them apart. The panelists had little or no idea about how non-profit arts organizations develop or how to measure success. Instead, the panel’s facilitator didn’t feel empowered to correct any statement that was untrue. Since many of the panelists only read some of the proposals, the main presenter of the proposal is crucial to the process being fair. The current system needs to be trashed and re-invented from scratch. I think it would be better to pay specialists in the non-profit arts world to decide the recipients of grants of $50,000 than to continue operating the current system, that is of the same caliber as Russian Roulette.

KH: It’s complex. We would have a different set of troubles if we did that. I think we need a funding ecosystem where some grants are peer reviewed and other grants, especially for longer term organizational development grants where you need to build a relationship with the funder, are not. It’s weird to be subject to a new panel every year. For certain projects the concept of peer review panels makes sense, but the panelists need to be paid better. Low paid panelists reproduce certain problems that a more engaged panel wouldn’t. I just wrote a grant to the Arts Commission, my first one in many years, where I’m the only lead artist, and I got the lowest score I’ve ever had.

My bias is that I don’t talk to any funders ever. I don’t respect what they’re doing. They’re probably good people, but I’m lying to them constantly. If we talk, I’m going to reveal what’s actually going on, which is that the people getting the most funding are the biggest liars who have learned to game the system, not the best artists or the most curious and rigorous artists or the most dangerous to capitalism artists.

JJ: Yeah, the performative nature of contemporary American politics has completely taken over. Apparently, there’s no such thing as truth. All that’s left is the hollowed-out and endlessly repeated rhetoric that disguises the basic corruption of the status quo.

KH: Right. But the thing is, Jeff, you had some really strong critiques that were totally supported by your community. When you were pointing out the white supremacy in local and national arts funding, you were supported by a community of artists who were coming from the left, including many people of color. What’s happened now is that the language that you helped generate is literally now being used against people, to strangulate and stagnate the community.

Three years ago, the California Arts Council basically said you had to pass a political obedience test to even apply. You had to write an approved racial equity statement to even be able to submit your grant. I spent days on it. I got so deep that by the end I felt humiliated because of how much I cared about it. Eventually I took the racial equity statement that the CAC used as their model, copied it, changed two words, sent it back, and it was accepted by the system. Proof that it was nothing but a fake gesture.

JJ: Many organizations of color should just say “I’m Black; what else would you like to know?”

KH: Right. My org helps a lot of queer artists of color to write grants and they’re like, “Do I actually have to tell them I’m Black and I’m gay in every answer?” I say, ‘Unfortunately, yes, you do.’ Then white applicants, who mostly don’t even mention that they’re white in their bios or mission statements, have to portray themselves as anti-racists who prioritize racial justice. If you don’t say it, you’re not going to get the money. That has little or nothing to do with producing good art.

In fact, if you’re doing good art, you probably won’t get funded at this point because the people judging you have no idea what good art is. And yes I know there’s no such thing as good art, and that “good art” has been used against politically-inspired artists, especially non-white and queer artists. Despite the difficulty of determining quality I still think we should be concerned about it, constantly undermining normative understandings of good and interesting and valuable, but not giving up on art itself, on quality, rigor, experimentation, impact on the field. Undoubtedly there are great and curious artists getting CAC money, but there’s a disconnect between what they write and what they do.

If I can lie,it means anyone can lie, even though I actually do create art with as much integrity as I can put into action. But we are also seeing new works that have no actual community involvement and the people of color who they supposedly “collaborated” with had no actual power.

JJ: Let’s go back to Contraband. What I remember most about Contraband was that it was a multidisciplinary performance where there was nudity and contact improvisation. Did that come out of Contraband, or out of Sara? Or did that come out of somewhere else?

KH: There was definitely skin in Contraband shows, but there was very little actual nudity. That was more in the works that happened around it, from artists like me or Jess Curtis who were more connected to sex positive scenes, queer scenes and sex worker culture. In Feminist and queer performance art there is a vital relationship to the body. Carolee Schneemann pulling a scroll from her pussy predates so many of us. But she leads directly to Karen Finley, who leads to different queer artists, and Ron Athey, who’s cutting himself and bleeding as an HIV positive artist. I love artists who transcend the boundary of the flesh; orifices and bodily fluids are important in my work.

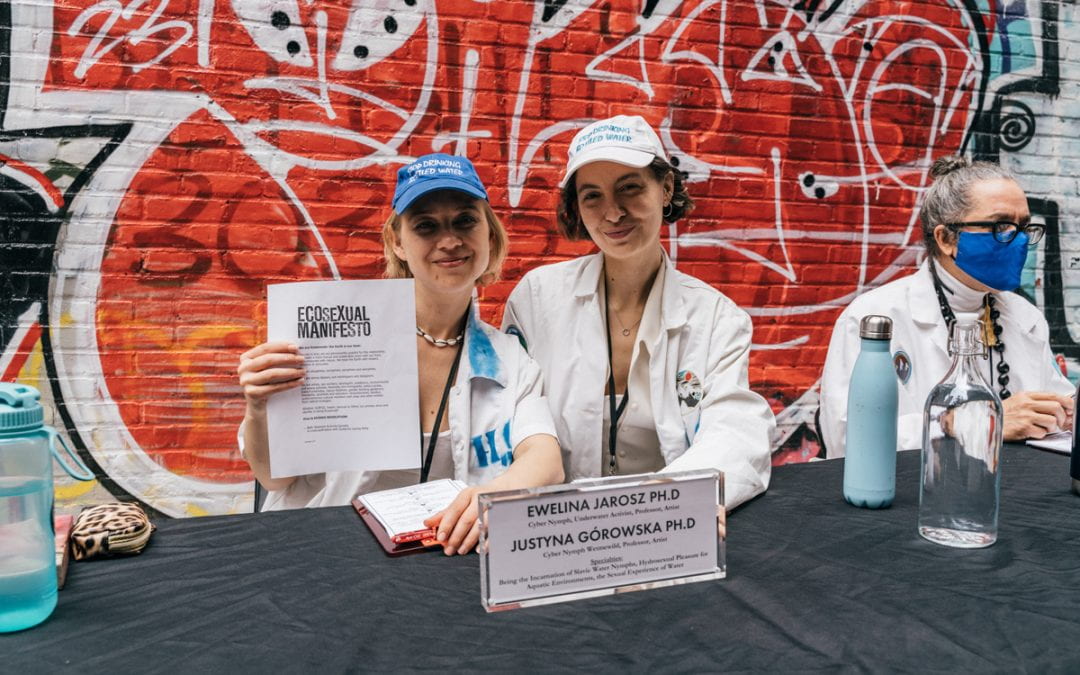

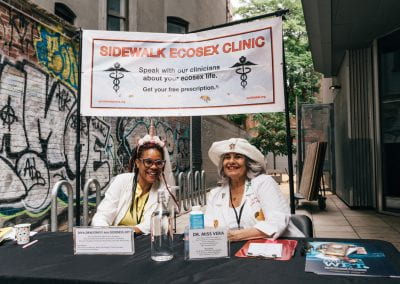

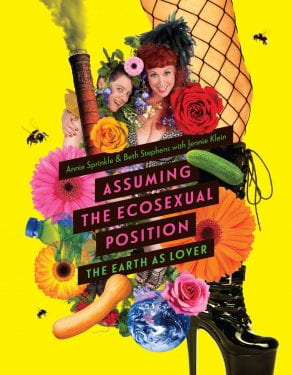

Annie Sprinkle, you changed the world. You’re the most visible sex worker turned performance artist in the history of the world. There are really important things that happened in the long-running and constantly evolving post-porn project. We can see all of this movement between the Public Cervix Announcement and your Pornstistics, that asked questions such as “What if I added inch by inch the dicks I’ve sucked, would they equal the height of the Empire State Building?”

There is a combination of shamelessness and self-reflection on the shadow sides of the porn industry that inspired thousands of people. This is feminist work. We see an independent woman fighting for the autonomy of her own body, rejecting shame as a colonial, patriarchal construction that tries to keep people down. The whole notion that sex work should upset us on moral grounds is bullshit propaganda that comes out of a colonized mindset. Queers have different ways of seeing this through sex-positive, feminist and queer legacies.

Sara is impacted by these worlds, but in the same way that she defends herself by refusing the disciplinary boundaries around dance, she also refuses to join any movement. She’s never felt at home anywhere. Part of her practice has been the idea that she is disconnected from everything and therefore she is in this liberated space. Faustin Linyekula, from Congo (DRC), one of the most important contemporary African dancers, who in his lifetime had experienced multiple names for the country of his birth once said, “The only country I know is my body.” He was also responding to political trauma on the body and refusing to participate in any particular identity.

Contact improvisation is a dance form that was first named in 1972, but comes out of a series of experiments impacted by 1960s era feminism, hippy culture, and critiques of power and hierarchy. It’s an anti-hierarchical form with no gender roles and no leadership, neither a choreographer or a man leading a woman in a duet. The ideals of 1960’s feminism, gay liberation, and left politics were adapted into this free-flowing dance form. At its worst, it’s a hippie/new-age modality that really should fade away. At its best, it’s one of the most radical technologies we have for rethinking intimate human relationships at the level of the body. It encourages us to improvise and negotiate how we touch and play with each other.

Sara was exposed to contact improv and it blew her world apart because she came from a dance world where the choreographer is in control, there is a correct technique, and you do it until you kill yourself. There’s a recording of Sara saying that when she found contact improv, it was the first time she could push against a man and be met in her physical strength and not pay for it, not be punished for it, not be hit back for it.

Sara brought contact improvisation into modern dance and merged it with psycho-spiritual practices from different teachers. She studied every new-age and alternative healing modality on Earth and she synthesized all of these practices. And she keeps moving. The work she makes today doesn’t look like what she made 10 years ago, or 30 years ago.

Her refusal to be categorized should be seen as queer, revolutionary and liberatory. I was rejected for many of my early grants because the panelists would say “that’s not dance”. They just didn’t get it. But Sara and Contraband did change the world. Now people recognize what I do in the dance world. It’s also why I had a home in Europe for half my life, because there you can be rewarded for rigorous approaches to conceptual and experimental dance where you don’t have to lead with a political statement to get gigs or funding.

Now we’re constantly divided by bizarre tensions: in the funding world, the weaponization of woke language; in the current struggle for Palestinian liberation, the revisionary and weaponized notion of anti-semitism. If you cared about antisemitism, you wouldn’t back the extremist right, white supremacists who have been anti-semitic since day one. You wouldn’t back an apartheid regime or justify a war that kills children, or support putting our tax dollars into the war machine instead of into the arts.

JJ: It’s all connected. In 1980, I was the person who ran the Census in San Francisco. That gave me a really good understanding of who lives where. But when I started looking at my clients such as Theatre Rhinoceros, the Women’s Philharmonic and the Mime Troupe, there was a disconnect: most of the arts money was spent entertaining affluent white people!

KH: Not just any white people, to be clear: it was the upper class and the wanna-be upper classes who were being served… affluent!

JJ: The 1980 Census found that San Francisco was a city where people of color were the majority. I saw that maybe 1% of the money was going to queers, 1% was going to Black people, 1% was going to Latinxers and almost 2% to Asian Americans. The pure tokenism of it all kept bugging me. So by 1985, because I demographically knew who San Franciscans were, it became clear that the vast majority of the residents were not even taken into consideration. When it was time to hand out arts funding, the arts were perceived as something for the well-educated, the well-bred and the well-fed.

KH: Let me do a slight intervention here. I think if you only lead with race, you create some of the problems that we want to avoid. If you refer to the audience of the opera as white and then refer to Contraband as white, you’ve really done a disservice to the actual liberatory politics that we want to uplift. What’s significant is that the core audience for the opera is people who own their own homes, while the artists and the audiences of Contraband were low-income people living precariously in rental housing. Sara Shelton Mann has been working with economically disenfranchised artists for her entire life. But there’s nowhere to write that on a grant application. Contraband was primarily an all-white troupe because of how segregated the dance scene was in the 1980s, but Contraband didn’t create that segregation, and with no money to pay artists Contraband didn’t really have much power to change it.

What’s different about the Bay Area compared to New York is that the vast majority of artists of color in the Bay Area did not work in experimental forms for many years. In New York and Paris they did. But in San Francisco, Black artists did Black dance. In Contraband white modern dancers had to work for almost no pay and attend a minimum of 3-hour long rehearsals 3 times a week; there was only a very tiny group of freaks that would and could do that. And none of us at the time were living off family funds… We worked in bakeries, restaurants, teaching dance, driving trucks and mostly did not eat out except in Mexican restaurants that served burritos.

JJ: I know that the end of Contraband was complicated. Sara herself told me that the problem was that she could not raise the money to support the company.

KH: What happened is that the world gentrified and San Francisco hyper-gentrified. You could no longer make work here and not pay everyone. Sara had a highly functioning, amazingly productive, world changing company from 85 to 95. It’s also part of her working style to build things up, destroy them, and start again. It’s a very creative practice but it’s not sustainable.

JJ: But I don’t think that was true in the 80s. I moved here in 1979 and it was cheap. Sara told me that financing the Company became impossible.

KH: Right. But what year do you think that happened?

JJ: I thought it was 1990. You’re saying it’s 1995.

KH: Yes. The company continued with Mira: Cycles all the way until 1995. When Sara moved here around 1980, she saw that Margaret Jenkins and Brenda Way had companies; she wanted one too, but she was never supported and couldn’t figure out why.

JJ: She wasn’t part of the 4-person sisterhood: Kary, Margie Jenkins, Brenda Way and Chris Hellman, the Chair of the Ballet Board.

KH: It wasn’t just that sisterhood. I would guess that all of them were raised with more money and more family coherence than Sara. She never assumed (or lucked into or sought out) that she would meet a man, marry him, have kids, get a college job or broad social support. Sara is the ultimate lesbian archetype without actually being a lesbian. She’s the crone witch who inspired thousands of children but never had a family of her own. She sacrificed family-making and financial security to build a world through dance.

JJ: Sara’s inheritors were people like you and Jess Curtis and others who started doing original work. After Contraband split up, didn’t you become a member of another collective?

KH: Yes, CORE was made up of 5 people, the three “boys” from Contraband – Jess Curtis, Jules Beckman, me – plus Stanya Kahn and Stephanie Maher. We made one show, Entertainment for the Apocalypse (originally titled Psychic Driveby),which we performed in various places around the Bay, and in Salt Lake, LA, New York and Germany. It was similar to Contraband in that there were no political slogans on the stage, but the work was deeply political in terms of how we were thinking through the politics of the body, anti-hierarchical leadership, and what it meant to commit to expressing yourself. That’s not exactly true because both Stanya and I wrote and performed more explicitly political texts, but still not slogans. We produced work with no funding. We built everything ourselves. We performed in gorgeous shit-ass warehouses. I remember the conclusion of an early CORE performance: I was in heels and a gold dress swimming in the toxic dump of Islais Creek/San Francisco Bay while the other artists were on a pier holding giant flaming torches. You couldn’t use straightforward social justice language to describe the work. But you saw people who refused to be categorized by boundaries, women who were totally fierce in their relationship with the men on stage, grief about the death of revolutionary politics, and performances in alternative community spaces that we took over and transformed for our site-specific work. The body-art-collective as a site of activist ritual performance. The body and performance as a site of healing. CORE existed for about 4 years and then dissolved as we all moved on.

JJ: Where did you go after that?

KH: Jess Curtis, Jules Beckman and I moved to France to be in Cahin-caha, cirque bâtard, an experimental circus that had money to pay us. Stephanie Maher moved to Berlin and created a dance space in a former squat, and had two kids. Then they bought land and made Ponderosa, an influential rural community and art space outside of Berlin with workshops and residences for experimental art and improvisation, which has linked San Francisco and Berlin for the last 20 years. Stanya Khan became a successful filmmaker and visual artist. She lives in LA, has a child, was in the Whitney Biennial, and had a big show at the New Museum in NY.

JJ: Wasn’t she a dancer also?

KH: She started off in dance, but was always also a writer, visual artist, and activist. She was raised in a 1960s militant radical household, so she’s always engaged politics in her dance and visual art. She moved into filmmaking with her former partner, Harry Dodge, and they exclusively worked in film for years. A lot of Stanya’s notable works are experimental films that are primarily exhibited in galleries and museums. They’re brilliant.

JJ: I remember she was in the second or third National Queer Arts Festival.

KH: Her work at that time was more performance art than dance. In one piece, she did a monologue about her mother while she took apart, cleaned and put back together a real gun on stage, next to a vase of jasmine flowers.

B&A: Tell us about 848 Community Space.

KH: 848 was founded in 1991, when Contraband was still going strong.This couple had a community art space that they didn’t know how to make sustainable. They were going to get rid of the space, so we decided to take it over. We kept the name 848. I was at the very beginning of my work in sexual healing and sex radicalism and I said, ‘I’ll co-found this place with my straight friend Michael Med-O Whitson, but it’s going be a very gay space.’ 848 ran for over 10 years on Divisadero before it became Counterpulse on 9th Street, and then another ten years before it moved (and purchased!!!) 80 Turk St in the Tenderloin.

From the outset we tried to make a space that wouldn’t be identified with a single community. The very first Trans performance art and photography shows happened at 848 because no other venue would host them. Before there was a Black Choreographer’s Festival, we held a mini-weekend festival of all Black choreographers. Before there were any Asian dance festivals, we had weekend performances showcasing Asian choreographers and dancers. There was a contact improv jam every Tuesday. Carol Queen and Patrick Califia held sex parties at 848. There was a sex worker support group that met there and produced performances. There was a sex worker art festival. And buddhists met there weekly for silent meditation at 7am.

It was a very queer, sex positive space, but the people involved in that side of it often didn’t know that it was also a vibrant contemporary dance space. Some of that vibe emerged from Contraband, which mixed contact-improv with social justice politics, feminism and queerness. Both CounterPulse and 848 were very liberatory spaces for experimental and politically-activated performance.

San Francisco had been a hotbed of experimental work, but only now is there a thriving community of BIPOC artists doing experimental dance and performance. Look at the work that Amara Tabor-Smith has done for the last 10 years, or rupture collective, or the work that Jess Curtis lifted up with some of the emerging Black artists fiscally sponsored or produced by his non-profit Gravity. Gabriel Christian and Chibueze Crouch of oysterknife just did a massive Black mass at Grace Cathedral called mouf/full. These experimental Black artists are referencing Black folkloric forms and Black diasporic culture, but they also see themselves as contemporary artists who don’t want to be constrained by their racial identity, but liberated.

JJ: Where did Jessica Robinson go? Is she still around?

B&A: She became the brilliant Executive Director at CounterPULSE.

KH: Jessica Robinson Love rocked CounterPULSE. She took it from this ragtag, barely funded group and stewarded the transition of 848 to CounterPulse, from Divisadero St to on 9th & Mission. Jessica grew the staff in a way that empowered queer women’s leadership. She networked with funders and secured grant money to pay rent, staff, and to innovate expansive programming. With a team, she pioneered all kinds of amazing anti-racist and pro-immigrant dance projects. Jessica supported a very expanded concept of dance.

KH: Jessica Robinson Love rocked CounterPULSE. She took it from this ragtag, barely funded group and stewarded the transition of 848 to CounterPulse, from Divisadero St to on 9th & Mission. Jessica grew the staff in a way that empowered queer women’s leadership. She networked with funders and secured grant money to pay rent, staff, and to innovate expansive programming. With a team, she pioneered all kinds of amazing anti-racist and pro-immigrant dance projects. Jessica supported a very expanded concept of dance.

After 10 years, just as the organization was going to move to the new building, she stepped down. I imagined her thinking, “Whoever takes on the ED job is taking on a project for 10 years and I’m going to bow out.” She went into philanthropy. She was never that solid as an art maker, but her creativity thrived in arts administration and executive leadership. Jessica left CounterPulse and the arts to move towards funding larger social justice projects.

JJ: Did she leave San Francisco?

KH: No, she stayed. She really dropped out of the art world and went onto the field of international development. She passed the leadership of CounterPULSE to Julie Phelps, who literally came into the art world in the Bay Area as Jess Curtis’s assistant and then mine. Julie stewarded CounterPULSE for 7 years and raised 7 million dollars to buy that building. She further developed the organization’s queer, anti-racist, feminist, and neighborhood-based politics. With her team she created programs of art for poor people and for disenfranchised and marginalized populations. Jessica Robinson Love and Julie Phelps have left an extraordinary legacy in San Francisco.

JJ: I noticed that soon after the Cultural Equity Grants Program started operating, most of the organizations Grants for the Arts wouldn’t fund got funded by the Arts Commission, and then subsequently got funded by Grants for the Arts. That was the new approach for many people.

KH: Yeah, many people did that, including me.

JJ: I could never figure out why you were shut out in the first place.

KH: Because the head of Grants for the Arts was a fucking idiot and a control freak. No one will say that publicly, but this can go into your archive. The GFTA panel recommended me for funding and she blocked it. This isn’t only about me. GFTA criteria was biased towards more professional and more normative organizations, gatekeeping who could advance in SF arts. GFTA didn’t give enough money to small organizations, while prioritizing millions for the large white led and white serving art institutions. For years GFTA offered the only steady annual operating funds, which is what you need to be able to hire staff. When you’re just getting project funds through the CAC or the SF Arts Commission, you can’t build an organization. You can’t build power.

JJ: I understand that. But in 1993 the reality was that Grants for the Arts was the biggest arts funding source. Back then, Blacks, Latinos, AAPIs, Native Americans, women, queers, together received about 8% of the agency’s funding and almost half went to large organizations.

KH: The creation of the SFAC Cultural Equity Grants Program was brilliant and goes down as one of your central legacies Jeff. Your tombstone will have a lot of text, but that will be one of the statements on there. Without Jeff Jones we wouldn’t have had the Cultural Equity Grants program and its very radical impact on the Bay Area’s arts community or its global impact because what happens in San Francisco affects the world.

JJ: Yeah. No other city has set up a Cultural Equity Grants Program anywhere else, but by osmosis it seems we won that battle.

KH: Now grants across the US use the language of racial equity and radical inclusion to lift up disenfranchised people because of the pioneering work that you and others did with the San Francisco Arts Commission.

JJ: At one point, after I wrote my first report on hew agency, Kary Schumann contacted the Board Chairs of my clients and told them that they needed to fire me.

KH: She’s part of a long line of nepotistic, jealous people in the San Francisco city government. But I need to say, at one point you said, “ Close GFTA and leave only the Arts Commission.” I fought you on that behind the scenes. I did not agree.

JJ: I’m very happy I lost that battle because I’ve noticed that some GFTA decisions are now actually better than a lot of those happening at SFAC.

B&A: How long was Kary Schumann the head of Grants for the Arts?

JJ: From 1978 to 2019: 41 stagnant years. When London Breed got elected to a full 4-year term as Mayor, the first thing she did was fire Kary.

KH: Kary was a tyrant, but her replacement Vallie Brown was a completely inept person who was involved in the pettiest shit-ass nepotistic politics in San Francisco history.

JJ: Annie and Beth got funded. That’s all I’ll say.

KH: We are not better off with Vallie Brown and it’s wonderful that she’s leaving the job. The best thing to happen with GFTA recently is that they’ve realized it should be a multi-year grant. So now the applications will be for two years. Many countries with more intelligent arts funding give multi-year grants to established artists and arts organizations.

The Republicans have basically gone to war with San Francisco and have declared the city’s death on their national news. It’s the combination of real politics and the politics on the street, from San Francisco not taking care of its houseless people to the Republican’s war on the City’s reputation. The decrease in tourist dollars equals a decrease in GFTA money.

JJ: Yes. The amount available to the city is unknown right now. San Jose adopted that 2-year approach 10 or 15 years ago. I could never figure out why San Francisco didn’t follow suit. The California Arts Council has those absurd state and local partner programs which are a total waste of money that should go to artists instead. Each one of the 56 counties gets a minimum of $75,000. What do they do with it? Nobody knows.

B&A: How important have grant writers been to you, Keith?

KH: Grant writers have never been useful to me because either they cost too much money or they don’t understand my work. So I have learned to write grants in opposition to grant writers. I’ve always been very inspired by Jeff Jones and I’ve followed his work very closely, but I was never the right candidate for him to write my grants.

JJ: That’s untrue. I wrote the MAP proposal that funded you.

KH: One grant, yes, and only because I was part of National Queer Arts Fest. But in general you were not my grant writer and the grant writers that my friends worked with all charged too much and wrote extremely generic bullshit, which of course worked but I wasn’t yet prepared to compromise like that. I tried working with Nancy Quinn and a few other people when I had some money. Every one of them failed for me. They tried to fit me into boxes that were not real. If I used any of my own language, I was immediately unfunded. So I had to fight my way into the grant world and in the last 10 years I’ve really enjoyed the money that has produced all my projects and it has allowed me to support hundreds of other artists.

B&A: We are so glad you’re getting the bigger bucks now, Keith.

JJ: In the early nineties, there were a number of radical political factors at play. Frank Jordan was running for Mayor. He went to the Castro and a bunch of people hijacked his shoes and displayed them in the front window of the Castro’s Queer bookstore. Right before that, when the governor vetoed the gay & lesbian rights bill, a bunch of people marched down to the state building and set it on fire. I was there.

KH: Me too. I was not in the front line, but I was two steps behind. When the barricades went through the window, I was standing right there cheering.

JJ: Then right after that, there was the Hunky Jesus controversy. And there was the controversy over the minister who Mayor Jordan appointed to the Human Rights Commission who said that queers should be stoned to death because that’s what the Bible says. It was really amazing to be in City Hall watching people from our community screaming at the Mayor and the Board of Supervisors. They knew they had to do something. You were still doing 848 then, right?

KH: Yeah, we started in ’91. I think we were also very much in that 1990s zeitgeist. There were all these different trajectories through the 1980s, including ACT UP, Queer Nation, Lesbian Avengers, and other groups. But there were also hundreds of smaller groups, collectives, and artist collectives.

There was a massive queeruption or queer cultural uprising all over the Western world in response to the political repression of gay men and queers during AIDS. When people realized that the government would let you die and actually participate in your death, that was a radicalizing moment when a huge political shift occurred. It’s not unlike what’s happening right now around Palestine. Watching Biden’s regime trying to silence dissent and seeing the big universities surrender to Congresswoman Stefanik’s McCarthyite trials has literally empowered the protestors. They have nothing to lose now. The government is more concerned about people saying “from the river to the sea” than about the fact that the US is buying the white phosphorus bombs the Israelis are dropping on Palestinian families.

In the early 1990s, the first waves of massive gentrification affected cities. Embattled artists and queers who needed cities to survive were being pushed out. There was the AIDS activism and the feminist sex wars of the 1980s. But by then, those battles were over at the street or community level. The people leading the 1990s intersectional feminist movement were anti-racist and pro-sex and understood the class politics of the sexual body.

People don’t realize it, but we were having early discussions of antiracism and sexism in queer politics too. Every single ACT-UP and Queer Nation chapter had to ask, “Are the white gay men in charge, or are we gonna let women be in charge? Are we going to let people of color speak and lead?” Every chapter had to face structural racism and sexism in their organizing. The diversity we have today resulted from those struggles, even if many of those fights seemed petty and annoying.

The last thing I’ll say is that there were aesthetic impacts too. The cultural revolution in response to AIDS and the zeitgeist of class politics, race politics, gender and sex politics, produced an extraordinary amount of art and culture. The legacy of those lines of inquiry and artistic production are still very activating today.

JJ: Yeah, what was happening in art happened in politics. In the early 1990s it was almost anarchy. We weren’t afraid and we didn’t care if straight people didn’t like Piss Christ, Robert Mapplethorpe’s photos or the Hunky Jesus contests on Castro Street on Easter Sunday. It was a bigger movement that took many different forms. Everything seemed to converge: Queer Nation, the Transgender Rights Ordinance, the mayor’s shoes being ripped off, the launch of the Cultural Equity Grants program, the defeated re-election campaign of George Bush Sr. It was an extraordinary moment of queer politics.

KH: A book could be written about the history of the unpermitted marches in San Francisco. I’ve been here long enough to watch multiple generations wake up to the fact that you don’t actually need, and generally shouldn’t ask for, permission to march. The Dyke March became legitimized through arts funding and got permits afterwards, but not at the beginning.

We, my Circo Zero co-worker Alley Wilde and I, produced an event last year called Queer Joy. It was a very off the grid thing where we got different performers to perform along Valencia Street in alleyways and parks. We traveled to each site with a sound system and a group of people waving these beautiful flags made by Monica Canilao, a collaborator of mine who also works with Annie and Beth. The police came and asked, “Where’s your permit?” We said, “You must be new here. We don’t need one. Keep us safe or go away. Or hang out and enjoy the art!” And they admitted, “You’re right. You don’t need a permit.” You don’t need a permit to walk down a street in San Francisco if you’re too numerous for a sidewalk: it’s freedom of expression and you have a right to do it. I’m from the anarchist school of culture, so I would do it anyway.

B&A: What unique contribution do you think you made to San Francisco’s art history?

KH: I think I helped foreground an anti-disciplinary approach to experimental performance and to pioneer a mashup of the sex-positive world with the art world and with the world of far-left politics. I brought those things together and nurtured a legacy that is still in progress. I also pioneered “no one turned away for lack of funds.” I advocated for it starting in the 1980s and now it’s a norm in many places in the Bay Area.

B&A: Thank you for all that. What more do you hope to achieve, if anything?

KH: I have a lot of artistic ideas I’d still like to explore. I want to find ways to bring together the work I’ve done around dance, anti-racism, sexual healing, intimacy and pleasure healing. I would like to build more bridges between dance and performance and the sex and intimacy work that includes trauma informed consent and new ways to practice and innovate more ethical and free relationships between humans, as well as between humans and all beings and the earth itself. I think about capitalism politically and as a system of relationships that we need to redesign through practice. It’s not about taking down leaders, but about creating new political systems by creating new forms of human relationships. And I want to spend more time in water, dancing and healing in water.

B&A: How do you feel about trigger warnings for dance performances?

KH: I’m definitely disappointed that the bar for trigger warnings is so low. In 2023 CounterPULSE wanted to post a trigger warning for potential nudity in my performance with Ishmael Houston-Jones, in a venue I originally co-founded as a sexually explicit performance space. I do understand how some younger queers are thinking and feeling, especially the trans or nonbinary people with their different ways of processing gender dysphoria and gendered abuse. I don’t think a nudity warning, for example, should happen for dance or performance art. Especially for elder gay, politically radical, artistically experimental artists who have been naked on stage for 40 years. But I do recognize the importance of certain kinds of trigger warnings.

In early feminist theater, there was a real question: if your work was anti-rape, are you allowed to show a rape on stage? Feminist theater has now hit a point where it was no longer useful to show rape on stage because it pushes too many people into their traumas without giving them a way out. This is constantly an issue in film. If you reproduce the slavery era in a movie, should we see brutal whipping or should it happen off-screen? What do we lose or gain if we don’t acknowledge it? There are reasons to think about the potential for art to trigger trauma, but when trigger warnings happen at the very lowest common denominator, they’re actually a form of surveillance and control that feels neither democratic nor liberatory.

I think “safe space” as a political strategy is a dead end. I think we need to do more work, not only around safety, but around resilience, risk assessment, and being able to work with trauma.

B&A: We agree completely. You’ve been an artist on the cutting-edge doing radical work and sexually-oriented work. Do you have any guilt or remorse over any “mistakes” you may have made?

KH: I wouldn’t be human if I hadn’t made some mistakes and I wouldn’t be a good human if I couldn’t own up to them. I should have tried to institutionalize myself in the funding world earlier than I did, but my anarchist tendencies kept me from doing so. In terms of both race and gender politics, at different points in my career I have overstepped my bounds as a white male artist. I do recognize that I did things that hurt people’s feelings and hurt some relationships. There are a few occasions where I just exploded and burnt things down or provoked more than made sense to the context when I should have found a more subtle way to move forward, but mostly I regret not being more radical and louder. Oh and sometimes I really regret that I didn’t save and invest any money.

B&A: As you reflect on your contributions to the arts, and the challenges you’ve overcome, what advice or insights would you offer to emerging BIPOC and LGBTQ artists today.

KH: The first thing I would say is to put aside a minimum of $1,000 per year into savings for retirement. Next, I’d say have no shame about gaming the system that was literally structured to oppress you. You’re allowed to lie. You’re allowed to misrepresent. You’re allowed to double dip. You’re allowed to, as Remi Charlip asserted and practiced, make the same work twice and simply change its name.

Alley and I have had to convince many artists of color that in grant writing they’re allowed to bend the truth, exaggerate, even lie and cheat. Grant guidelines do not want you to write what many artists really want to write: “We want to get together with some excellent people and develop new ways to love each other and lift up each other’s creativity. We’re dancers and musicians who love a good show but we’re not sure what will happen. Most likely there’ll be a show, but if not, your meager $20K or $50K will be well spent supporting artistic experimentation that reimagines white supremicist capitalist heterocis patriarchy. Oh and by the way here are samples from the beautiful work last year and the year before.” You wouldn’t believe the contortions we go through to rewrite that proposal in exactly the right number of words and characters, with necessary yet repetitious assertions of our commitment to racial equity. Artists of color are so much more familiar with being surveilled and being targeted, of needing to be respectful and follow bureaucratic rules, while white people get away with a lot more. I really try to empower younger artists to disrespect the government and to disrespect bureaucracy when it’s not serving them. You’re allowed to speak out of both sides of your mouth. You’re allowed to lie on paper.

The third thing I’ll say is that your community and your political movements are beautiful inspirations and holders of your work. Be connected to political movements. Develop an ethical ground for your actions.. If your overall intention is to lift up your community and to lift up a revolution against colonial shame of the body, then say whatever you need to get the grant! Stay radical and experimental and uncontainable and ever changing.

JJ: I’d like to have a longer conversation with you about the current quagmires that we’re in around funding and politics, and how we’re in a period of American history where there doesn’t seem to be any ethical or moral backbone anymore.

KH: I tend to stay away from the idea of morals and I go to ethics, because I want people to have an ethical base for what they do, more than a moralistic sense of right and wrong. So yes, I think we need political ethics. We need to actually understand what feminist ethics look like, what a kind of queer ethics or anti-racist ethics or de-colonial ethics look like, and ground ourselves in those kinds of movements.

B&A: Thank you so much for sharing your life experience, thoughts and your survival strategies Keith.

JJ: Yeah, this was great.

KH: Love you people. Good luck. Goodbye.

B&A: We are also concerned that the people who made this arts funding history started dying before this history has been documented or preserved. So we are creating this archive as a historical record. With all the push-back against diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI), we think it’s important for artists, elected officials, educators and community leaders to be able to say, “Hey, they did this in San Francisco. Maybe we can do it here too.”

B&A: We are also concerned that the people who made this arts funding history started dying before this history has been documented or preserved. So we are creating this archive as a historical record. With all the push-back against diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI), we think it’s important for artists, elected officials, educators and community leaders to be able to say, “Hey, they did this in San Francisco. Maybe we can do it here too.” When Wallflower broke up and evolved into the Dance Brigade, Krissy Keefer and Nina Fichter hired Sara to make new work with them, and I got to be Sara’s assistant. They were the very first people in the local dance community to embrace Contraband. They brought us into Furious Feet: The Dance Festival for Social Change that they organized in the 80s and 90s.

When Wallflower broke up and evolved into the Dance Brigade, Krissy Keefer and Nina Fichter hired Sara to make new work with them, and I got to be Sara’s assistant. They were the very first people in the local dance community to embrace Contraband. They brought us into Furious Feet: The Dance Festival for Social Change that they organized in the 80s and 90s. Anyways, many of the artists who were attracted to Sara were very politically engaged. Kim Epifano came out of the Dance Brigade. I came out of different anarchist scenes. Nina Hart was also very involved in anarchist and feminist politics. I was obviously queer from the late 80s onwards, and was extremely involved in ACT UP and Queer Nation; both crucial to the queeruption aka cultural and political uprisings in response to AIDS.

Anyways, many of the artists who were attracted to Sara were very politically engaged. Kim Epifano came out of the Dance Brigade. I came out of different anarchist scenes. Nina Hart was also very involved in anarchist and feminist politics. I was obviously queer from the late 80s onwards, and was extremely involved in ACT UP and Queer Nation; both crucial to the queeruption aka cultural and political uprisings in response to AIDS. JJ: Yes, it feels to me like we are back to where the arts world was in the mid-1980s, when we had words like “multiculturalism” and nobody knew what it meant. The California Arts Council is a really great example. They have a so-called “peer review” process, but it’s not the peer review system of 40 years ago that was facilitated by specialists in the arts discipline, who knew the significant artists and organizations and who was empowered to interrupt and correct any mis-statements of facts made by the panelists.

JJ: Yes, it feels to me like we are back to where the arts world was in the mid-1980s, when we had words like “multiculturalism” and nobody knew what it meant. The California Arts Council is a really great example. They have a so-called “peer review” process, but it’s not the peer review system of 40 years ago that was facilitated by specialists in the arts discipline, who knew the significant artists and organizations and who was empowered to interrupt and correct any mis-statements of facts made by the panelists. KH: Jessica Robinson Love rocked CounterPULSE. She took it from this ragtag, barely funded group and stewarded the transition of 848 to CounterPulse, from Divisadero St to on 9th & Mission. Jessica grew the staff in a way that empowered queer women’s leadership. She networked with funders and secured grant money to pay rent, staff, and to innovate expansive programming. With a team, she pioneered all kinds of amazing anti-racist and pro-immigrant dance projects. Jessica supported a very expanded concept of dance.

KH: Jessica Robinson Love rocked CounterPULSE. She took it from this ragtag, barely funded group and stewarded the transition of 848 to CounterPulse, from Divisadero St to on 9th & Mission. Jessica grew the staff in a way that empowered queer women’s leadership. She networked with funders and secured grant money to pay rent, staff, and to innovate expansive programming. With a team, she pioneered all kinds of amazing anti-racist and pro-immigrant dance projects. Jessica supported a very expanded concept of dance.

JJ: Marga: When did you move to San Francisco?

JJ: Marga: When did you move to San Francisco? My touring performances in Europe were the first time that I actually earned money as an entertainer. I worked with Lilith on and off. I think I went on a second European tour with them in 1981; then I came back to my job making omelets at the Acme. There was a publication back then, called Backstage I think, where you could find out about auditions. I auditioned for Les Nickelettes and worked with them on a couple of shows. That was basically my life from 1976 to 1982.

My touring performances in Europe were the first time that I actually earned money as an entertainer. I worked with Lilith on and off. I think I went on a second European tour with them in 1981; then I came back to my job making omelets at the Acme. There was a publication back then, called Backstage I think, where you could find out about auditions. I auditioned for Les Nickelettes and worked with them on a couple of shows. That was basically my life from 1976 to 1982. Donald Montwell and his boyfriend Jimmy managed the Valencia Rose. Donald was definitely one of my mentors, because I was still not sure if I wanted to be out. Did I want to risk not getting my own sitcom or anything like that? Which is what happened if you were out. Ellen was doing really well doing comedy in San Francisco, but she was not out.

Donald Montwell and his boyfriend Jimmy managed the Valencia Rose. Donald was definitely one of my mentors, because I was still not sure if I wanted to be out. Did I want to risk not getting my own sitcom or anything like that? Which is what happened if you were out. Ellen was doing really well doing comedy in San Francisco, but she was not out. I appeared in a Mime Troupe show called Crossing Borders. It was about Salvadoran immigrants and what they were going through. I went on tour with that show. That’s where I met Stacy Powers-Cuellar, who now runs Brava Theater. Maria Acosta played my sister in the show, or a cousin or something. It was a great experience to work with them. But I didn’t really have the chops, to be honest.

I appeared in a Mime Troupe show called Crossing Borders. It was about Salvadoran immigrants and what they were going through. I went on tour with that show. That’s where I met Stacy Powers-Cuellar, who now runs Brava Theater. Maria Acosta played my sister in the show, or a cousin or something. It was a great experience to work with them. But I didn’t really have the chops, to be honest. Instead, I wrote a show about lesbians in the media that I premiered at Josie’s and I had workshopped it at The Marsh. I was doing the show but I didn’t have all the lines. So, I had little cheat sheets everywhere. I wound up dropping my notes and they flew all over the place. I had to go down on my knees and just read them in front of the audience, which included Laurie E. Seid, and Kate Bornstein. They loved that I fucked up and kept going. From there, my show Pretty, Witty and Gay, got booked at the 1993 Whitney Biennial.

Instead, I wrote a show about lesbians in the media that I premiered at Josie’s and I had workshopped it at The Marsh. I was doing the show but I didn’t have all the lines. So, I had little cheat sheets everywhere. I wound up dropping my notes and they flew all over the place. I had to go down on my knees and just read them in front of the audience, which included Laurie E. Seid, and Kate Bornstein. They loved that I fucked up and kept going. From there, my show Pretty, Witty and Gay, got booked at the 1993 Whitney Biennial. MG: That’s right. Tim Miller. Holly Hughes, Annie Sprinkle, my show Memory Tricks, which all got a lot of press attention. I was invited to be in the Sundance Writer’s Lab. It was the first time that Sundance invited playwrights. We would tell the filmmakers our play, our story, then talk about adapting it to a film. One night 5 of us soloists each did our shows on stage and everyone in the audience was a filmmaker. This really taught me the power of the solo art form.

MG: That’s right. Tim Miller. Holly Hughes, Annie Sprinkle, my show Memory Tricks, which all got a lot of press attention. I was invited to be in the Sundance Writer’s Lab. It was the first time that Sundance invited playwrights. We would tell the filmmakers our play, our story, then talk about adapting it to a film. One night 5 of us soloists each did our shows on stage and everyone in the audience was a filmmaker. This really taught me the power of the solo art form.

JJ: So when you started Wallflower, did you perceive what you were doing as performance art?

JJ: So when you started Wallflower, did you perceive what you were doing as performance art? KK: When Wallflower moved from Eugene, Oregon to Boston in 1981, we had been touring all over the United States, in Europe and Latin America and our work occupied the intersection where lesbian feminism meets solidarity work, exemplified by Chile’s Pinochet and many other US-propped up dictators across the globe. Lesbians were at the center of most solidarity groups supporting the liberation of Nicaragua and El Salvador. Our work married these two struggles on stage and there was an audience for it wherever we went.

KK: When Wallflower moved from Eugene, Oregon to Boston in 1981, we had been touring all over the United States, in Europe and Latin America and our work occupied the intersection where lesbian feminism meets solidarity work, exemplified by Chile’s Pinochet and many other US-propped up dictators across the globe. Lesbians were at the center of most solidarity groups supporting the liberation of Nicaragua and El Salvador. Our work married these two struggles on stage and there was an audience for it wherever we went. JJ: I think some of these earlier pieces and events you were producing resonated. What about Furious Feet?

JJ: I think some of these earlier pieces and events you were producing resonated. What about Furious Feet? KK: I feel like in dance everybody works with everybody. All the dancers move through many different choreographers because nobody can afford to pay a company except for the ballet, Michael Smuin, Alonzo King and Sean Dorsey. But most dancers move back and forth.

KK: I feel like in dance everybody works with everybody. All the dancers move through many different choreographers because nobody can afford to pay a company except for the ballet, Michael Smuin, Alonzo King and Sean Dorsey. But most dancers move back and forth. KK: I think definitely The Wallflower Order. Creating that collective was the beginning. I think creating the GRRRl Brigade too. Besides that, I think starting the Lesbian and Gay Dance Festival and the first Festival presenting sky dancers– “Women who Fly through the Air.”

KK: I think definitely The Wallflower Order. Creating that collective was the beginning. I think creating the GRRRl Brigade too. Besides that, I think starting the Lesbian and Gay Dance Festival and the first Festival presenting sky dancers– “Women who Fly through the Air.” KK: You got demonized super bad. I remember when someone came to meet with me—she had just been assigned by the NEA to be Dance Brigade’s Advancement Consultant. They told me “You gotta stop working with Jeff.” I didn’t understand what was going on. But I do remember looking at a finished grant that just sat on the floor of the closet because you had written it. It was that you were calling Kary Schulman’s Agency (Grants for the Arts) racist and they were all coming after you.

KK: You got demonized super bad. I remember when someone came to meet with me—she had just been assigned by the NEA to be Dance Brigade’s Advancement Consultant. They told me “You gotta stop working with Jeff.” I didn’t understand what was going on. But I do remember looking at a finished grant that just sat on the floor of the closet because you had written it. It was that you were calling Kary Schulman’s Agency (Grants for the Arts) racist and they were all coming after you.

B&A: When did you get involved with Idris Ackamoor and Cultural Odyssey?

B&A: When did you get involved with Idris Ackamoor and Cultural Odyssey? I remember being in Berlin with Cecil Brown, the writer. I was doing some nude work in Berlin and this crazy woman came to the club. She was taking us over to her house for dinner, but then she pulled out a gun. Cecil said, “Whoa, what the hell?” And she said, “Do YOU have a gun?” I think the goddamn gun went off.

I remember being in Berlin with Cecil Brown, the writer. I was doing some nude work in Berlin and this crazy woman came to the club. She was taking us over to her house for dinner, but then she pulled out a gun. Cecil said, “Whoa, what the hell?” And she said, “Do YOU have a gun?” I think the goddamn gun went off. RJ: Well, The California Arts Council awarded the Sheriff’s Department a grant to hire me as a resident artist in the Women’s jail. My job was to go into the jails and teach aerobics to incarcerated women. Looking back, I realize that they just didn’t know what else to do with all of these women in jail.

RJ: Well, The California Arts Council awarded the Sheriff’s Department a grant to hire me as a resident artist in the Women’s jail. My job was to go into the jails and teach aerobics to incarcerated women. Looking back, I realize that they just didn’t know what else to do with all of these women in jail. JJ: The first Medea Project production was Reality is just Outside the Window. Your solo show Big Butt Girls, Hard-headed Women was also about incarcerated women. You were doing something very different than everyone else in the theater world. Medea wasn’t just a solo performance. It was a reality-based performance featuring both professional actors and prisoners. The weird thing was that the audience couldn’t always tell who was a prisoner and who was a professional actor.

JJ: The first Medea Project production was Reality is just Outside the Window. Your solo show Big Butt Girls, Hard-headed Women was also about incarcerated women. You were doing something very different than everyone else in the theater world. Medea wasn’t just a solo performance. It was a reality-based performance featuring both professional actors and prisoners. The weird thing was that the audience couldn’t always tell who was a prisoner and who was a professional actor. B&A: When is that piece going to be up, Rhodessa?

B&A: When is that piece going to be up, Rhodessa?

JJ: What year did you become the director of the GLBT Historical Society?

JJ: What year did you become the director of the GLBT Historical Society? B&A: According to Wikipedia, Tranny Fest became the San Francisco Transgender Film Festival, and it was the world’s first trans Film Festival. And we were there! Memories are full.

B&A: According to Wikipedia, Tranny Fest became the San Francisco Transgender Film Festival, and it was the world’s first trans Film Festival. And we were there! Memories are full. The wave of trans activism that started in the ‘90s in San Francisco, and later fueled a wave of cultural production, came out of that sensibility. It was a way of meeting the moment with regard to the impact of AIDS—trans women of color engaged in survival sex work had the highest infection rates of any demographic—as well as contesting the historic relationship between trans life and an often transphobic cis-gay and cis-lesbian community.

The wave of trans activism that started in the ‘90s in San Francisco, and later fueled a wave of cultural production, came out of that sensibility. It was a way of meeting the moment with regard to the impact of AIDS—trans women of color engaged in survival sex work had the highest infection rates of any demographic—as well as contesting the historic relationship between trans life and an often transphobic cis-gay and cis-lesbian community. I’m thinking, too, of someone like Jayne County, once a drag queen from the South who hustled her way up to New York City doing sex work, became part of Charles Ludlam’s Theater of the Ridiculous, and became a major punk icon with her band Wayne County and the Electric Chairs before she transitioned. They had this amazing song called If You Don’t Want to Fuck Me, Baby, Then Baby, Fuck Off. She brought this total, in-your-face punk sensibility to the work that she was doing. She titled her autobiography Man Enough to Be a Woman. She became a fixture at Max’s Kansas City, and her style influenced everybody from the Dolls to Bowie to Lou Reed to Blondie. She was an incredibly seminal cultural figure. Is that “trans art” now? I think so. By the time the 1990s rolled around, a late-career Jayne County put out an album called Transgender Rock and Roll. And she paints. She has a really interesting outsider-artist style.